2018

This post is a part of Hyunju Jang’s research paper, “An energy model of high-rise apartment buildings integrating variation in energy consumption between individual units” , published in Energy and Buildings, accessed by https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2017.10.047.

Building energy modelling methods have been required to be more accurate by taking into account variation in building factors affecting on energy consumption. However, modelling approaches for high-rise apartment buildings have often disregarded variation arising from individual apartment units. This study aimed to develop a building energy model of high-rise apartment buildings by integrating variation derived from individual apartment units.

The methods were designed in three steps: identifying unit-specific heating consumption in different locations; creating a building energy model, based on the physical characteristics of apartment units and identifying the influential heating controls on heating energy consumption; and integrating a new set of polynomial model of independent heating controls in units and their interactions between floors.

The result indicates that the averaged heating energy consumption of whole-building has a limited interpretation to represent the wide range of heating energy use in apartment units with different locations from 96 to 171 kWh/m2/year. The integrated set of polynomial model found that apartment units on lower floors need either higher set-point temperatures or longer heating hours than the probable heating control in the building-scale. Moreover, the accuracy of the model estimation is also improved to CV RMSE 5.6%.

Model framework

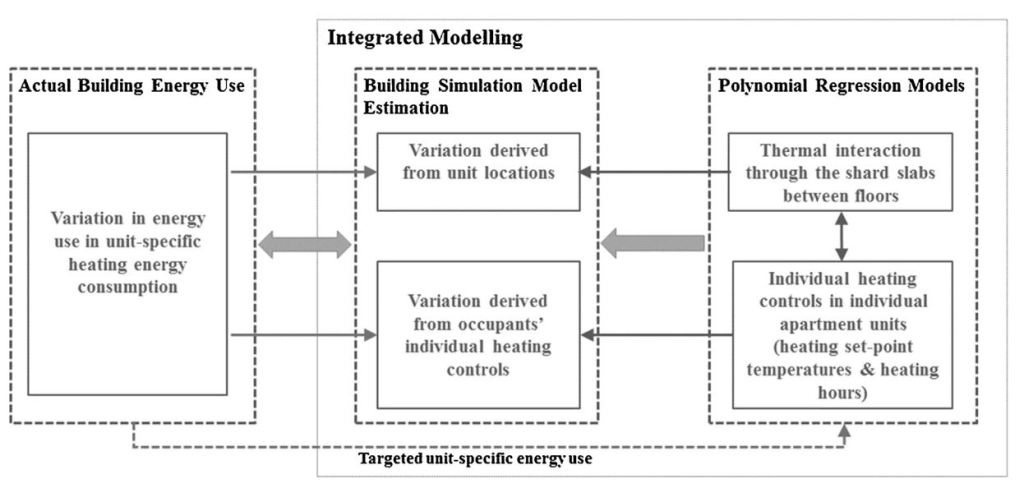

Fig. 1 describes the conceptual model framework integrating variation in energy use derived from unit locations and occupants’ heating controls in individual apartment units. It can be seen that the framework of the energy model is formed by three sections: (1) identifying heating energy consumption and its variation in individual apartment units with different locations; (2) creating a building energy model, based on the physical characteristics of apartment units in different locations and identifying the influential heating controls on heating energy consumption through uncertainty and sensitivity analyses; (3) integrating a new set of model for unit-specific energy consumption.

Figure 1 Conceptual model framework integrating variation in energy use derived from unit locations and occupants’ heating controls in individual apartment units.

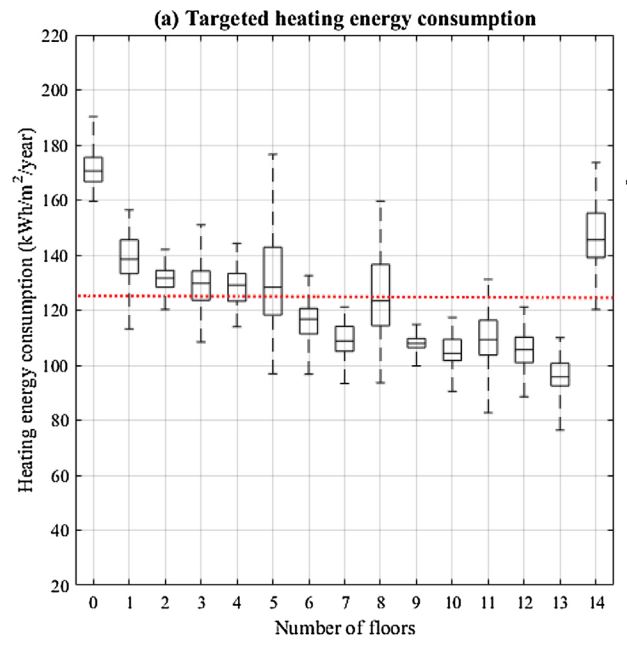

Figure 2 Comparison between the targeted heating energy consumption and the estimated consumption of the simplified energy model for the 15 apartment units on different floors: (a) Targeted heating energy consumption and (b) Estimated heating energy consumption.

As easily assumed, higher heating energy consumption on the ground and top floors, caused by the physical conditions, is clearly quantified. The highest heating energy consumption, 170.6 kWh/m2/year, is occurred on the ground floor, followed by 146.8 kWh/m2/year of heating consumption on the top floor as the second highest value. The other floors in-between the ground and top floors indicate a decreasing trend of the average heating energy consumption in accordance with higher floors. There is a certain degree of fluctuation among the average heating consumption on these floors. Heating energy consumption can be diverse depending on a level of standard deviation that exposes a level of dispersion on data. In other words, a building energy model for heating energy consumption can be easily failed if it does not take standard deviation into account.

Fig. 2(b) indicates the result of the simplified energy model estimations with the uncertainty analysis of the probable occupants’ heating controls. The average value of the simplified energy model is 104.0 kWh/m2/year (Fig. 2(b)) which is about 19% different from the targeted heating energy consumption (Fig. 2(a)), 123.2 kWh/m2/year. However, the current simplified energy model (Fig. 2(b)) shows its vulnerability to the possible heating controls in individual apartment units and the limited interpretation of reflecting the targeted unit-specific heating energy consumption in Fig. 2(a). Therefore, the model needs to be sharply calibrated to reflect the targeted energy consumption in each apartment units.

Integrating relationships with individual heating controls in units and thermal interactions between floors through the shared slabs

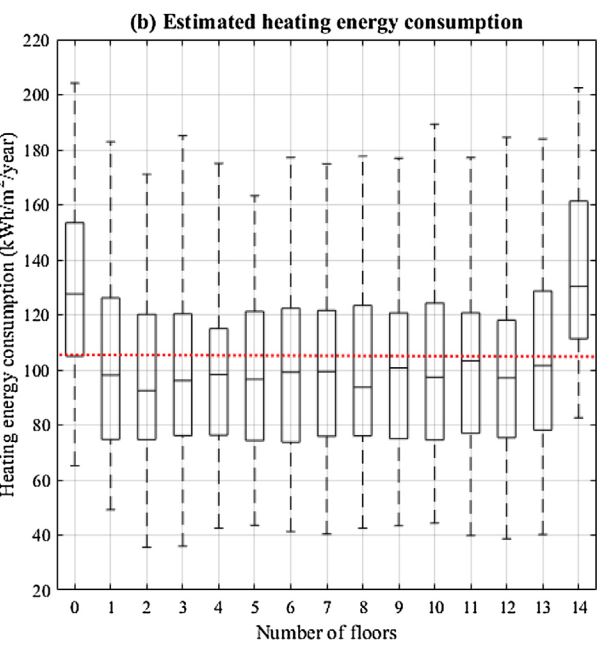

The correlation coefficient analysis allows determining relevant independent variables in changing the unit-specific heating energy consumption in the simplified energy model. Fig. 3(a) shows the results of correlation coefficient analysis. the analysis determines two correlated conditions for the unit-specific heating energy consumption. One is heating controls in apartment units where heating is operating (heating set-point temperatures and heating hours), another is heating set-point temperatures between floors.

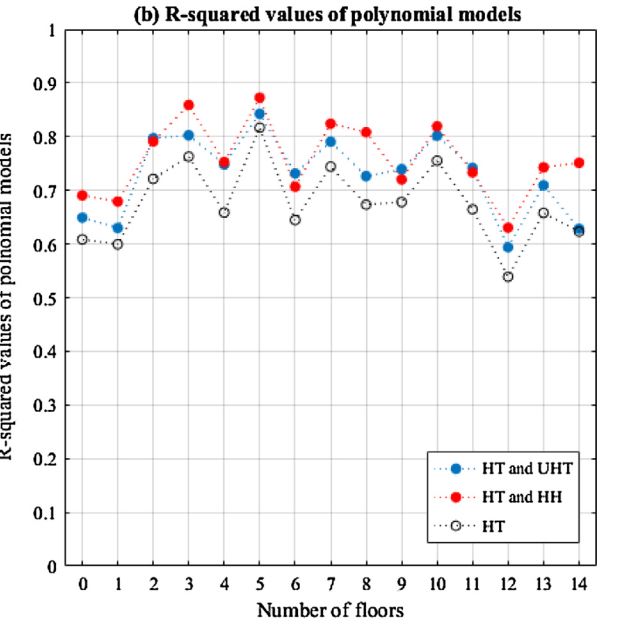

Figure 3 Exploring influential independent variables in unit-specific heating energy consumption: (a) Results of correlation coefficient analysis; (b) R-squared values of polynomial models: HT (Heating set-point temperature in apartment units), UHT(Heating set-point temperature in apartment units on an upper floor), LHT(Heating

set-point temperature in apartment units on a lower floor), and HH (Heating hours in apartment units).

This is also proved by R-squared values of polynomial models, as indicated in Fig. 3(b). These two conditions are integrated into the polynomial regression models to be used for further predictions: heating controls in each apartment unit (blue dotted lines in Fig. 3(b)) and heating set-point temperatures between floors (red dotted lines in Fig. 3(b)). Compared to the polynomial models with one variable, heating set-point temperatures (white dotted lines in Fig. 3(b)), polynomial models with two variables have higher R-squared values. Adding one more independent variable either heating hours or set-point temperatures on an upper floor raises R-squared values. However, the different is not significant enough to disregard the impact of the set-point temperatures between floors.

Model establishment

This section specifies the new model establishment of heating energy use in individual apartment units with respect to the two significant determinants. Polynomial models were developed by integrating two conditions, heating controls in apartment units and the interactions of heating temperature controls between floors. Firstly, various degrees of polynomial models from a linear to more complicated designs were evaluated by comparing the goodness of fit with R-squared values of models and Root-Mean-Square-Error (RMSE). Secondly, the best-fit models were used to calculate the sensitivities of two independent variables in order to achieve the targeted heating energy consumption in each apartment unit.

Polynomial models of heating controls in apartment units

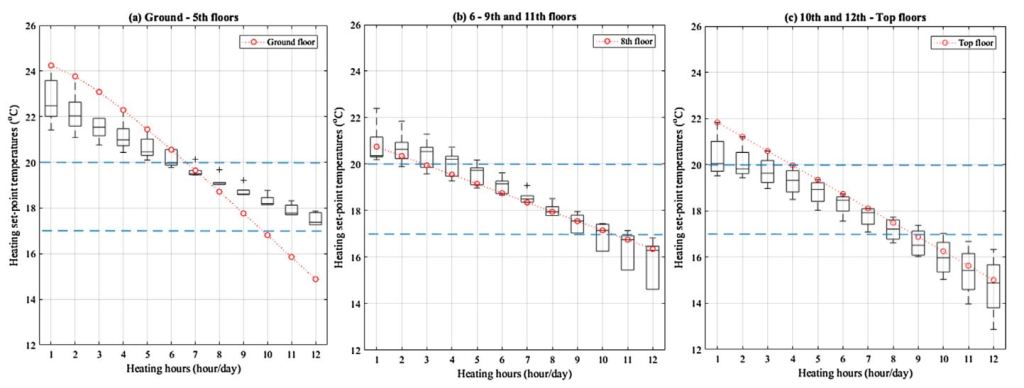

Fig. 4 demonstrates the change of heating set-point temperatures by increasing heating hours in the individual apartment units. The previous study with the whole building modelling estimated that 90% of probability of heating hours between three to six hours with 17–20 ◦C of heating set-point temperatures [16]. The authors reclaimed that the average heating set-point temperature for apartment buildings constructed in the 1980s with 18 ◦C rather than 20 ◦C, which has been widely applied in the conventional energy modelling. However, the unit-specific energy models with polynomial regressions indicate that the estimation with heating hours from three to six hours can be partially correct, as shown in Fig. 4(a)–(c).

Figure 4 The change of heating set-point temperatures by increasing heating hours in apartment units: (a) Ground to 5th floors; (b) 6–9th and 11th floors; (c) 10th and 12th – Top floors.

Apartment units located in lower floors need either higher set-point temperatures or longer heating hours in order to achieve the targeted heating energy consumption. Specifically,

energy consumption in apartment units on the ground to 5th floors

requires more than seven hours of heating with the range of heating set-point temperatures between 17–20 ◦C (Fig. 4(a)). In other words, heating set-point temperatures for these floors need to be risen up to 22–23 ◦C with less than six hours of heating. The heating consumption on the 6–9 and 11th floors is distributed between four and nine heating hours with 17–20 ◦C of heating set-point temperatures (Fig. 4(b)). The range of heating hours is achieved between three to eight for the consumption in apartment units on the 10th and 12th – top floors (Fig. 4(c)). The results indicate that heating controls in unit-specific energy models have the wider range of heating hours with 17–20 ◦C of heating set-point temperatures, which showed the 90% of probability in actual heating energy consumption in the whole apartment building in the district scale.

Polynomial models of interaction between floors

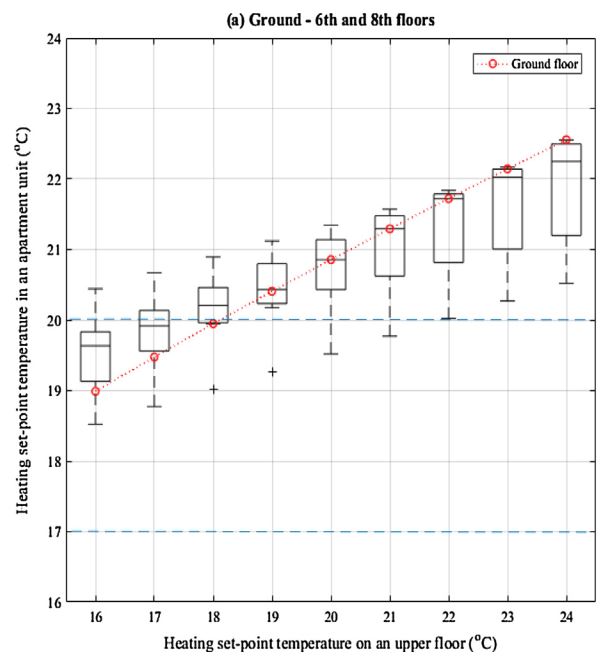

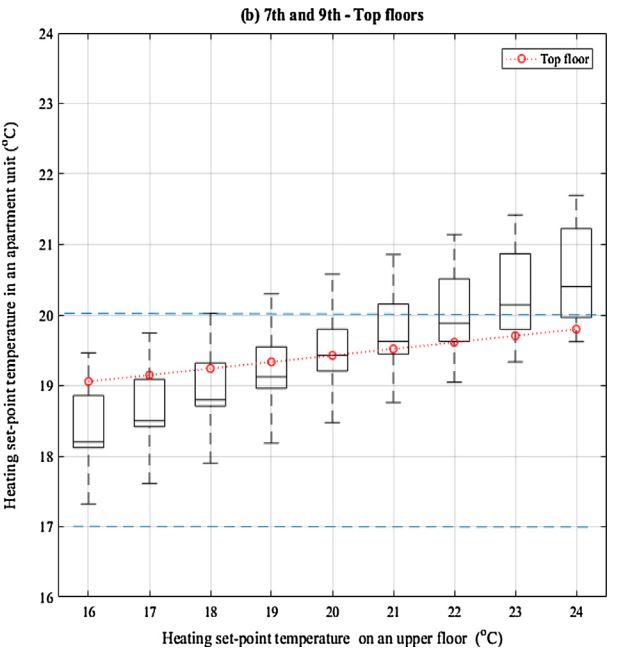

When higher heating energy use with the increase of heating set-point temperatures on an upper floor, heating energy consumption on the lower floor can expect to be reduced, because of heat transfer from the under-floor heating on the upper floor. To achieve the fixed target heating consumption, the heating set-point temperature in an apartment unit where heating is on is also increased with the set-point temperature increase on an upper floor.

The units from the ground to 6th and 8th floors show the possible range of heating set-point temperatures on an upper floor between 18.5 and 22.5 ◦C in accordance with heating set-point temperature on an upper floor (Fig. 5(a)). The possible range among the 7th and 9th to top floors is between 17 and 21.5 ◦C (Fig. 5(b)). This result shows that the temperature range between 17 and 20 ◦C, which is defined as the 90% probability of heating set-point temperatures with the whole building approach, would underestimate heating energy use in apartment units on the lower floors (the ground- 6th and 8th floors), whereas it could be relatively accurate for the upper floors (the 7th and 9th – top floors).

Figure 5 The change of heating set-point temperatures on an upper floor by increasing heating set-point temperatures in apartment units where heating is on: (a) Ground – 6th and 8th floors; (b) 7th and 9th – top floors.

Model demonstration

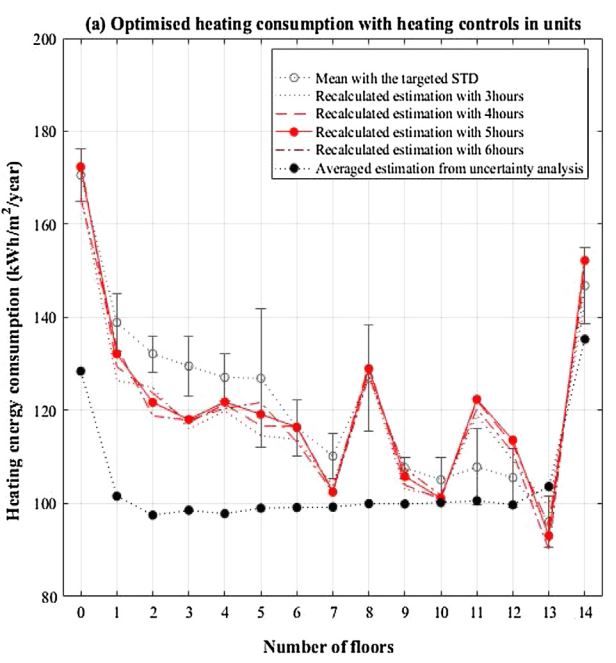

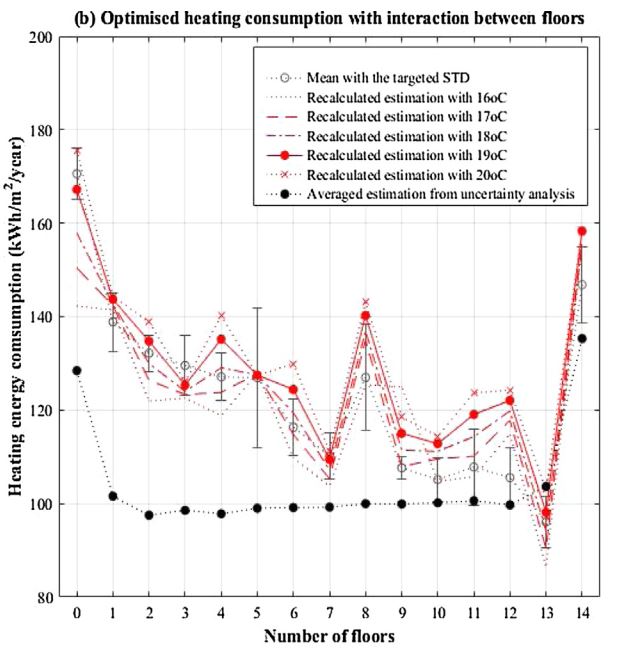

Through the model framework, new polynomial models optimised the heating controls of the individual apartment units to achieve the model estimations being more accurate towards the targeted/real heating energy consumption. This section inputs the optimised data-set of heating controls into the previous simplified building simulation models, and examined the results, as shown in Fig. 6. Fig. 6(a) depicts the recalculated heating estimation with the optimised heating controls in apartment units. With the polynomial models, the data-set of heating set-point temperatures was created when heating hours were from three to six hours. Fig. 6(b) describes the recalculated heating estimation with the optimised heating set-point temperatures between floors by applying heat set-point temperatures from 16 ◦C to 20 ◦C when seven hours heating.

Figure 6 Optimised building model estimation: (a) Optimised heating consumption with heating controls in apartment units; (b) Optimised heating consumption with interaction between floors.

At a glance, Fig. 6(a) and (b) inform more accurate heating estimation than the previous model estimation. Specifically, the best-fit model of heating controls in apartment units is the model with 5 h of heating with the least value of CV RMSE, 5.8%. Although the difference is not significant among the heating hours from three to seven hours, the model with eight hours heating demonstrates a higher difference from the targeted heating consumption. Unlike the models with heating controls in units (Fig. 6(a)), the estimated heating energy consumption on an upper floor in Fig. 6(b) responds more sensitively depending on the change of heating set-point temperatures in units where heating is on. The best-fit model of heating set-point temperatures between floors is the model with 18 ◦C with the least value of CV RMSE, 5.6%. The model with 19 ◦C may be more suitable for 6.7% although the level of CV RMSE is slightly higher.

Conclusions

This study focused on the variation of energy use arising from individual apartment units, and dedicated to developing an integrated approach to build the energy model with regard to the locations of apartment units and individual heating controls. This has been carried out integrating actual data into the existing building energy model, focusing on the physical conditions of individual units, in a building simulation, and then developing the new polynomial models with regard to the individual heating controls for further prediction.

The averaged heating energy consumption, 123.2 kWh/m2/year, in apartment buildings constructed before 1980 were varied by the locations of apartment units from 96 to 171 kWh/m2/year. The building simulation model was created by specifying the 15 individual apartment units placed in the different vertical locations. However, the model estimation revealed its vulnerability affected by the occupant-related factors. The new set of polynomial regression model was established and integrated to calibrate the inaccuracy of the simulation model estimation. Two building conditions of high-rise apartment buildings were used to create the polynomial regression models: heating controls in apartment units and heating set-point temperatures between floors. The set of polynomial model estimated the conditions of heating controls in order to consume the same amount of heating energy in the specific apartment units in the different locations.

With the set of the model interpreting heating controls in apartment units, it has been found that apartment units located in lower floors need either higher set-point temperatures up to 23 ◦C or longer heating hours (more than seven hours) than the probable range of heating controls for these apartment buildings (17–20 ◦C of heating set-point temperatures with three to six hours of heating).

With the set of the model for heating set-point temperature between floors, the lower floors from the ground to the eighth floors, except for the 7th floor, require higher heating set-point temperatures, above 20 ◦C although the heating set-point temperatures on the higher floors from the seventh to the top floor, except for the 8th floor, are the probable range.

Variation arising from individual apartment units may be disregarded if it is not a main consideration. However, considering individual units has been proved to reduce the inherent uncertainties of estimating energy consumption in apartment buildings. This can be expected to bring about more accurate outcomes with building energy simulations. Similar to this study, the variations in energy use in various other aspects have been considered in recent years, rather than using the average [30–32]. While for those considerations a number of models have been established using various methods [33,34], it is also useful to consider simplified mathematical approaches or empirical estimation methods, which will be the scope of further studies.

References

Find the list of the references, accessed by https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2017.10.047.