2018

The shophouse is a typical building type of Southeast Asian cities. Shophouses were built in Thailand since the mid-19th century but massively built during the postwar-economic-boom years of the 1960s and 1970s. Being simple, standardised, and practical in original plans and construction, many shophouses had beautiful sun-shading elements cast in concrete on their facades. Unfortunately, many shophouses nowadays deteriorate and do not fit many aspects of contemporary urban life. However, they can potentially be renovated to respond to present life styles of both their original and new residents, and benefit the city as a whole.

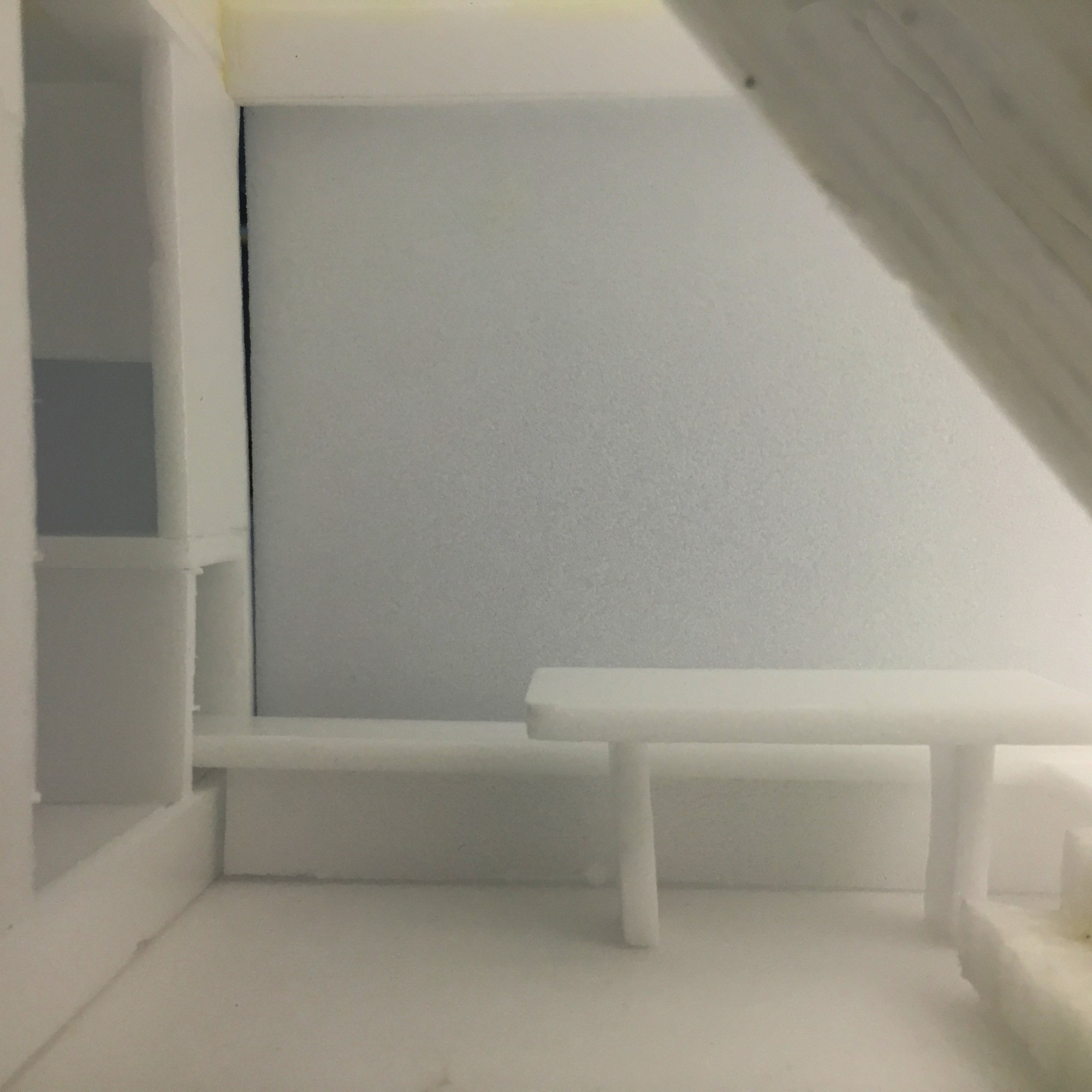

Fusinpaiboon and Jang explored the design that would make shophouse renovation easy and affordable. We did experiments on the design of a shophouse at Soi Sukhumvit 56, a typical residential neighbourhood about 10 km. from Bangkok’s central business district. We set the program for the 3.5-floor-and-a-rooftop shophouse as having a garage and an entrance hall on the ground foor; a mezzanine and the second floor as office spaces; and the third floor and rooftop as residential spaces.

Gaining insights from academic research studies and first-hand observations, we started our design process by reviewing all typical problems and issues related to old shophouses. Then we reviewed design solutions suggested by those research studies and case studies of shophouse renovation designed by fellow architects so far. We found that the following problems and issues were typically what needed to be improved:

· Hygiene and comfort as a result of limited ventilation and low penetration of natural light

· Lack of green space

· Uncontrolled alteration and extension that are normally against building regulations

· Problems related to the alterations of structure and building systems, such as plumbing and electricity

· Pollution such as noise and dust

· Lack of fire escape

We adapted and applied good solutions from the case studies in our design. More importantly, we also listed out extra issues previously absent or unclearly addressed in the case studies and tackled them with our design. The list came from our main aim to …

“… explore a way to make shophouse renovation as easy and affordable as possible. And that way should be able to be adapted and applied widely by the public.”

The list were as follows:

· The typically long-and-narrow spaces of shophouses, created by the fact that most shophouses’ floor plans have paralleling opaque walls with opening only at both ends, not only limited ventilation and the penetration of natural light, as critiqued by most research and design case studies, but also limited spatial perception of the inhabitants as if they lived in a box.

· The lack of communication and consideration among occupiers/owners in a same row of shophouses in doing each of their own alterations/extensions creates messiness, disorderliness, and the lack of unity of street facades. This undermined the uniqueness of the original designs of shophouses’ facades, often characterised by concrete shading elements, which could potentially be considered as an identity of Thai cities.

· Occupiers/owners’ lack of knowledge about how to renovate a shophouse and about the entailed cost and procedures related to design and construction. This issue raised a question about a suitable involvements of professionals, such as architects and engineers, builders, contractors, and construction permission from the local authority.

The above list emphasised our intention to engage with human’s perceptions of both private and public spaces. Together with the typical issues learnt from previous case studies, we finally set our design directions as follows:

· Opening up spaces both physically and perceptually not only to increase hygiene and comfort by allowing more ventilation and penetration of natural light but also to break the typically boxy spaces.

· Opening up spaces towards green space, if any, and/or bringing it in, while being aware of pollution, such as noise and dust.

· Renovating the shophouse within the limitation allowed by building regulations and involving local authorities as little as possible, or not at all, to minimise possible inconvenience.

· Simplifying the alterations and/or additions of structure and building systems, such as plumbing and electricity, to avoid both structural and maintemance problems, and minimise cost.

· Ensuring the presence of fire escapes

· Promoting the unity of street facades

The final design came after explorations of alternatives that responded to the design directions in different degrees. Starting from the facade design, we maintained the external frame of arches, the shading element of the original shophouse. We repainted them with a neutral colour used by an adjacent neighbour, while enlarging doors and windows on the inner edge for better ventilation, more natural light, and a wider view of the leafy neighbourhood on the opposite side.

By doing so, we altered the fenestrations according to what we believed to suit the users’ most while maintaining the frame, shared by adjacent shophouses in the same row to avoid an extreme disorderliness. We did not propose a strict uniformity of the street façade but envisioned a design that still allowed diversity and freedom while maintaining a certain level of unity.

We hoped to see neighbours sharing this idea, exploring possibilities of plans and fenestrations while maintaining the unity of the street facade. And we were glad that the neighbour on the left started to do that!