This post is a part of Hyunju Jang’s research paper, “Prioritisation of old apartment buildings for energy-efficient refurbishment based on the effects of building features on energy consumption” , published in Energy and Buildings, accessed by https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2015.03.027

2015

Since the 1970s the construction of high-rise apartments has been prolific across Asia. More recently, due to changes in legislation, there has been a growing trend towards refurbishment for those old apartments, however this has primarily focused on the economic benefits and rarely taken energy saving and the reduction of carbon emissions into account. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate what features in old apartment buildings need to be taken into account in refurbishment strategies. The method is threefold: evaluating energy consumption in old apartment buildings; identifying effective building features on energy consumption; and ranking the effects of building features on energy consumption. The results show that old apartment buildings have consumed excessive energy for space heating and cooling. Maximum 43.65 kWh/m2/year in space heating and 5.70 kWh/m2/year in cooling were reduced as a result of the transformation of eight building features, accounting for 70.9% of total variance in factor analysis. Three most influential features, which should be used to priorities for refurbishment schemes, have been identified by multiple regression analysis: the conditions of building envelopes, heating methods and the sizes of building units. Therefore, the priority should be given to these three features.

This study focuses on identifying old high-rise apartment buildings in South Korea which need to be refurbished to reduce energy consumption. Furthermore, the most efficient strategy of refurbishment will be identified by investigating building features and their effect on energy consumption in those apartment buildings. Three questions will be answered:

- What are the levels of energy consumption in old apartment buildings? Do these levels of consumption need to be reduced?

- Which features in old apartment buildings have affected the energy consumption?

- Which building features should be prioritised in refurbishment strategies in order to reduce energy consumption?

Methodology

The methodology is designed to analyse the impact of building features in old apartment buildings on actual energy consumption. The results will help to prioritise which building features can most effectively reduce energy consumption and thus guide the creation of refurbishment strategies. The method is threefold: evaluating energy consumption in old apartment buildings; identifying effective building features on energy consumption; and ranking the effects of building features to energy consumption.

Evaluation of energy consumption in old apartment buildings

Energy consumption in old apartment buildings was evaluated to determine the necessity of refurbishment to reduce energy consumption. The consumption in old apartment buildings was, therefore, compared to the consumption in apartment buildings which were certified as energy-efficient. To conduct this, old apartment buildings are defined by those which were constructed before 2001, a year when building regulations for the thermal conditions of apartment buildings was much intensified and building energy rating system was just established. Permission has already given for some of these buildings to be refurbished; others will be available to be refurbished in 2015 by a building regulation in South Korea [29]. In contrast, the comparison group of apartment buildings were certified as energy-efficient in an energy rating system set by Korea Land and Housing Corporation in South Korea [30]. The three values of energy consumption in the both groups were compared: total end-use energy consumption; space heating and electricity consumption by construction years; and monthly energy consumption for space heating and electricity.

Identification of building features affecting energy consumption

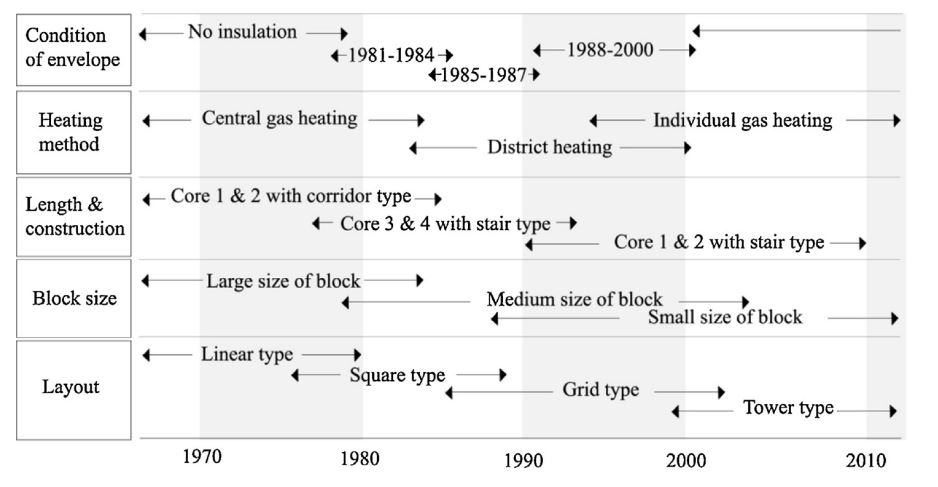

Building features in old apartment buildings were identified by reviewing previous literature and surveying existing old apartment buildings. To prioritise building features in refurbishment, this study was, particularly, focused on the transformation of building features rather than characteristics which are commonly found in all buildings. It is difficult to precisely divide time periods of each feature. Instead, this study used the dominant designs since the 1980s, as described in Fig. 1. Three distinctive trends are identified in the transformation of building features in old apartment buildings constructed before 2001.

Figure 1 Changes of building features in apartment construction of South Korea since the 1970s

Building Lengths

Building Layouts

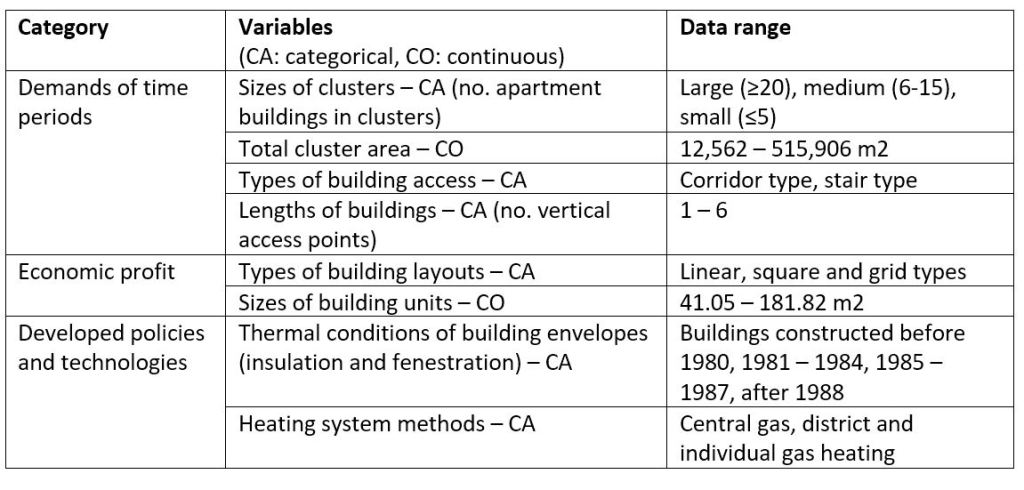

Table 1 Change in designs of building features in apartment construction in South Korea in pre-2001.

Table 1 indicates how designs of building features were transformed until 2000. This transformation of those building features was examined as to whether they affect actual energy consumption or not; thus effective building features on energy consumption were identified.

Old apartment buildings constructed in pre-2001

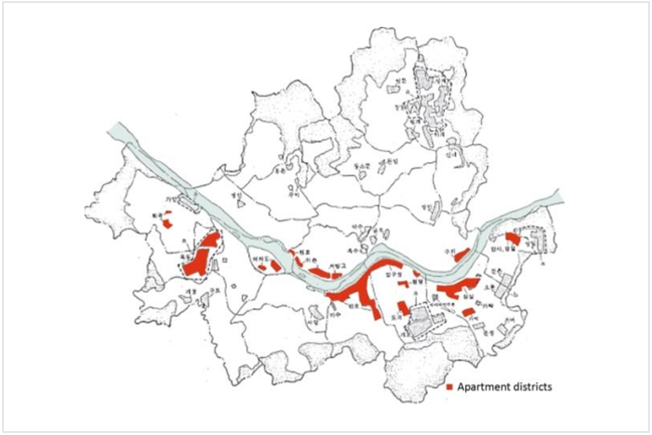

Total 189 apartment clusters with 1767 buildings (171,054 households) were selected as samples. The samples occupy 3.5% of the population size, 4,988,441 households [11,12] in apartment buildings constructed between 1976 and 2000 in South Korea. The sampling frame was designed with four sampling units: (1) construction years; (2) regions; (3) the number of floors; and (4) the availability of data on energy consumption. Firstly, apartment buildings which were built between 1976 and 2000 were only considered, because apartment buildings constructed after 2001 are regarded less urgent to be refurbished with an intensified building regulation, and constructed before 1976 are highly regarded to be demolished as low-rise buildings to rebuild high-rise buildings. Secondly, 16 apartment districts in Seoul were selected. The districts were established as parts of enormous housing construction projects between the 1980s and 1990s, leading the dramatic increase of apartment building construction. 60% of apartment buildings constructed before 2000 in Seoul were built in these districts [42]. Therefore, buildings in these districts have used to identify dominant characteristics built in that period. Moreover, these districts in Seoul are in the same climate zone, and the same thermal building regulations are applied to the buildings in Seoul and the central regions of South Korea; thus there would not be significantly different climate impacts in these districts. The impacts of microclimate such as heat island effects may give influence in energy consumption [43]. However, these possible impacts were taken into account in this study as building features related to building clusters. Third, apartment buildings with more than 10 floors were considered. This is because that refurbishment would be inevitable for the buildings which have more than 10 floors. As they were densely constructed, it is difficult to acquire permissions to demolish them in order to build super high-rise buildings under the current building regulations [13,44]. Lastly, the availability of data on energy consumption limited the samples in this study. 15.2% of apartment buildings which did not fill their energy bill records between 2011 and 2012 in AMIS were not counted in this study.

Energy consumption bills between 2011 and 2012 were collected from ‘Apartment Management Information System (AMIS)’. This system is organised by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MLIT) and managed by the Korean Housing Management Association (KHMA). A policy has been implemented under which all apartment buildings in South Korea should input their expenses into this system. The system displays the expenditure of each apartment building. However, there were some missing data on the energy bills of some apartment buildings in the system. These apartment buildings were excluded in the samples. The collected data from energy bills were converted from Won/m2 to kWh/m2. The conversion rates refer to those of the Korean Electric Power Corporation [45] for electricity and Seoul City Gas [46] for gas.

A comparison group of apartment buildings

Total 34 apartment clusters with 319 buildings (13,551 households) built between 2008 and 2010 in one district. The samples occupy 1.8% of the population size, 740,214 households [11] in apartment buildings constructed between 2008 and 2010 in South Korea. Five sampling units were used: (1) construction years; (2) regions; (3) the number of floors; (4) energy-efficient certificates; (5) the availability of data on energy consumption. Firstly, buildings built after 2001 were selected to compare energy consumption in old apartment buildings because those

buildings are relatively regarded as energy-efficient. Secondly, as climate conditions can have a significant impact on energy use in buildings, a district in close proximity to the districts in Seoul selected for the analysis of old apartment buildings was selected to minimise variation between the old and new samples. Thirdly, the same number of floors, more than 10 floors, was also applied. Fourth, the certified apartment buildings as energy-efficient in this district were only used in this study as mentioned in Section 2.1. Lastly, the availability of data limited to choose the samples like old apartment buildings. The certified buildings which did not fill their energy bill records between 2011 and 2012 in AMIS were not counted. Energy bill data were collected by the same method used for old apartment buildings.

Result

The results are illustrated by three parts to answer the three research questions in this study. The first part (Section 3.1) describes energy consumption in old apartment buildings built in before 2001 by comparing the consumption in the group of apartment buildings built between 2008 and 2010. The second part (Section 3.2) indicates building features affecting energy consumption in old apartment buildings. The last part (Section 3.3) quantifies the effects of building features to energy consumption.

Energy consumption in old apartment buildings

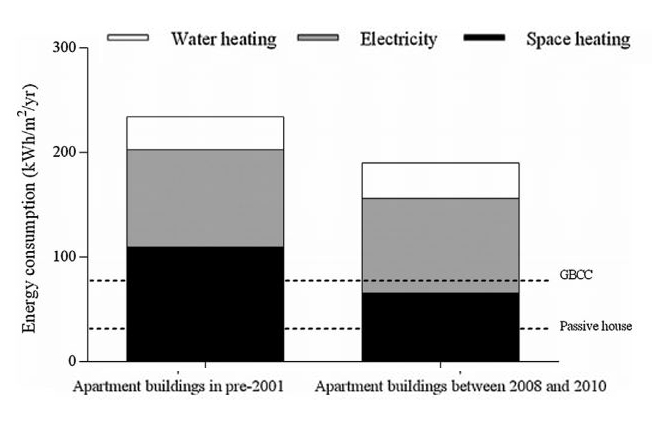

Figure 2 Total energy consumption of apartment buildings in 2011 and 2012

Fig. 2 shows a comparison of the total energy consumption of two groups of apartment buildings which are 234.2 kWh/m2/year and 190.0 kWh/m2/year, respectively. Both numbers are much higher than the 1st grade in energy rating systems set by Korea Green Building Certificate Criteria (GBCC) in South Korea (60.0 kWh/m2/year) [21] and Passive house standard (25.0 kWh/m2/year) [47]. This result shows that the energy consumption of both groups of apartment buildings needs to be

reduced to satisfy these energy rating systems. Despite excessive energy consumption, detailed consumption (separated by use) indicates different tendencies. Old apartment buildings consumed 109.6 kWh/m2/year for space heating whilst apartment buildings built between 2008 and 2010 only consumed 66.0 kWh/m2/year. On contrary, energy consumption of electricity and water heating did not have significant reductions in this period.

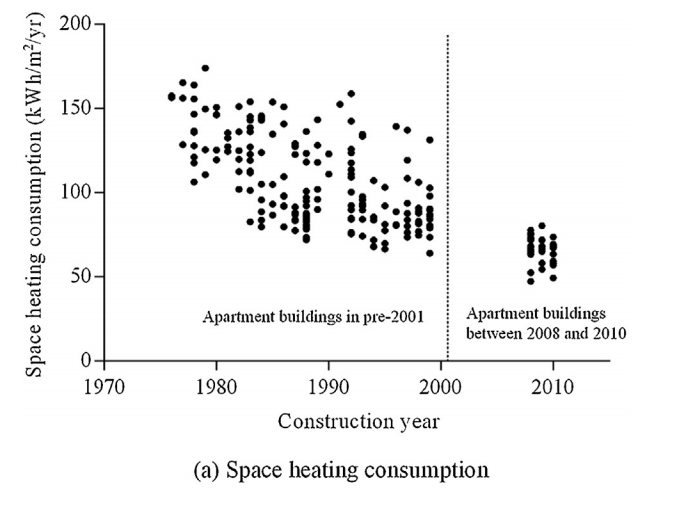

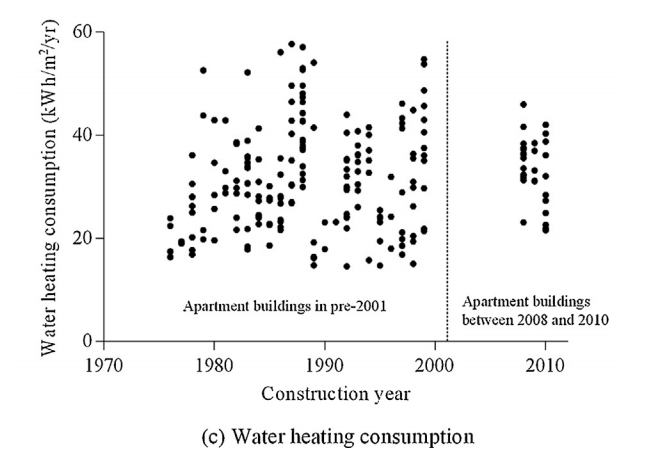

Figure 3 Energy consumption of apartment buildings by construction years: (a) space heating, (b) electricity, and (c) water heating

These tendencies are also shown in Fig. 3. The average energy consumed for space heating in old buildings has reduced by their construction years. 100% of old apartment buildings constructed before 1980 consumed more energy for space heating than the average of 108.8 kWh/m2/year, compared to 53% of old apartment buildings constructed in the 1980s. Only 20% of buildings in the 1990s and none of buildings constructed between 2008 and 2010 consumed above average energy for heating, these results suggest that apartment buildings built before 2001 have been able to decrease energy consumption efficiently regarding space heating.

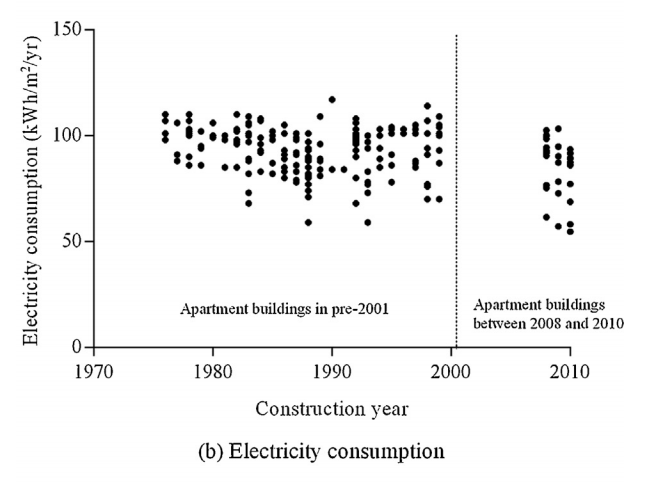

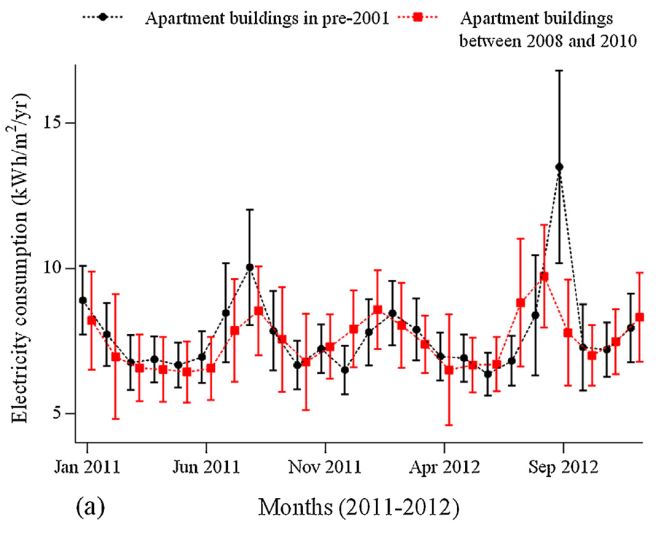

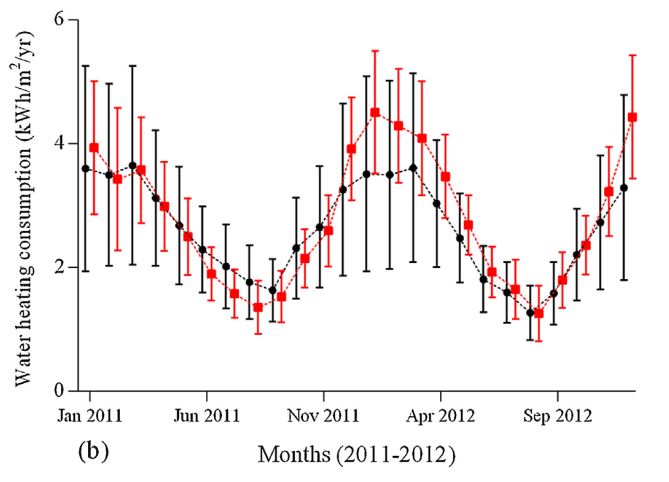

Figure 4 Monthly energy consumption between for (a) electricity and (b) water heating 2011 and 2012

Energy consumption for electricity was not reduced in this period; 92.2 kWh/m2/year of electricity was continuously consumed by apartment buildings in both groups. This can be explained by the everyday use of domestic appliances such as refrigerators, televisions and computers. However, Fig. 4 demonstrates that the summer use of electricity for space cooling in the old apartment building was especially high in August. In each month, there was only 0.05 kWh/m2/year difference between apartment buildings in the both groups, except for August when the gap was enlarged to 1.5 kWh/m2/year in 2011 and 5.7 kWh/m2/year in 2012.

Like electricity consumption, there was no significant reduction in water heating consumption; 32.6 kWh/m2/year of water heating was continuously consumed in both groups. However, the old building group demonstrated a higher relative standard deviation with 32.3% while 19.6% was for the new building group. Furthermore, these values are also higher, compared to space heating with 25.2% in old building group and 11.5% in new building group, and electricity with 15.3% and 11.9% in old and new building groups, respectively.

Overall, apartment buildings have been able to decrease energy consumption efficiently regarding space heating and cooling although there were not significant reduction in energy consumption for electricity and water heating. As identified in Section 2.2, physical conditions in apartment buildings constructed between 1976 and 2000 have been transformed. This would probably result in the changes of energy consumption in these buildings.

However, the effects of occupants could also be important factors to understand energy consumption in these buildings. Interestingly, residents living in apartment buildings in South Korea showed the extremely unified composition of households. 90% of apartment buildings’ inhabitants are parents with their offspring, and families with three or four members occupy 80% of households in apartment buildings [48]. Therefore, the general profiles of occupants such as the number of occupants and types of family may not give meaningful results explaining energy consumption. However, geographical segregations in residential areas caused by socio-economic factors such as the levels of income and education have been identified in South Korea [49]. Their effects would also be useful to identify the continuous energy consumption in electricity and water heating, and the large variations in water heating [50]. However, this study focused on the physical features of apartment buildings, which were described in Section 2.2, to create the efficient strategies for refurbishment.

Building features affecting to energy consumption

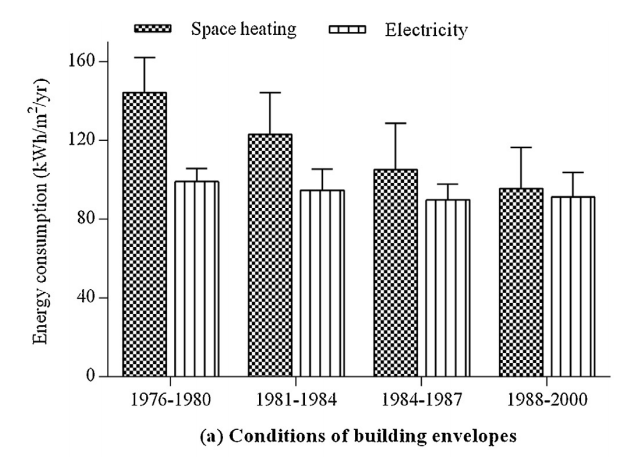

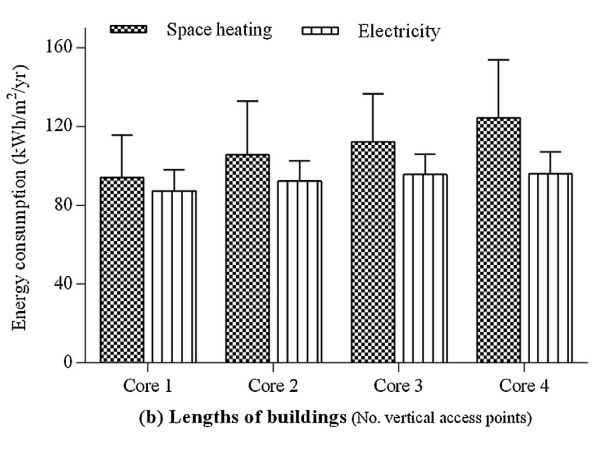

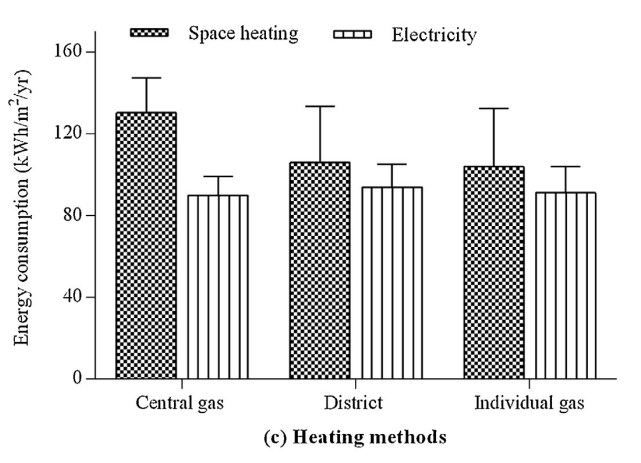

It can be seen that six of the eight features (Table 2) had an effect on energy consumption for space heating while little difference was found in electricity consumption. This can be explained by two opposing tendencies. As expected, one of these tendencies is that old apartment buildings constructed in the early stage consumed more energy than those constructed in the late stage. Three features, the conditions of building envelopes, the lengths of buildings and heating methods, accounted for this increasing tendency in energy consumption. This means that the transformations of the three features reduced energy consumption as seen in Fig. 5.

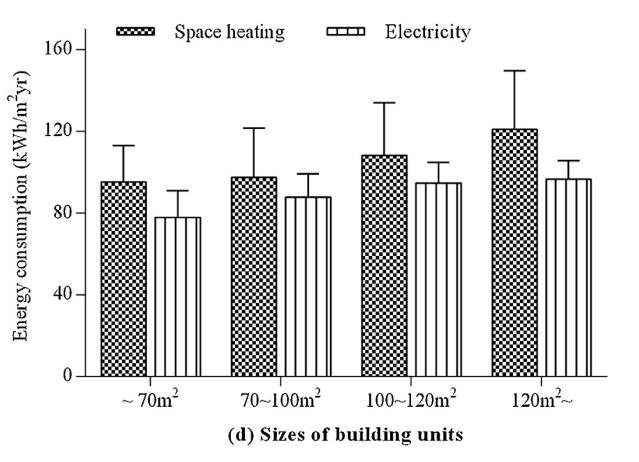

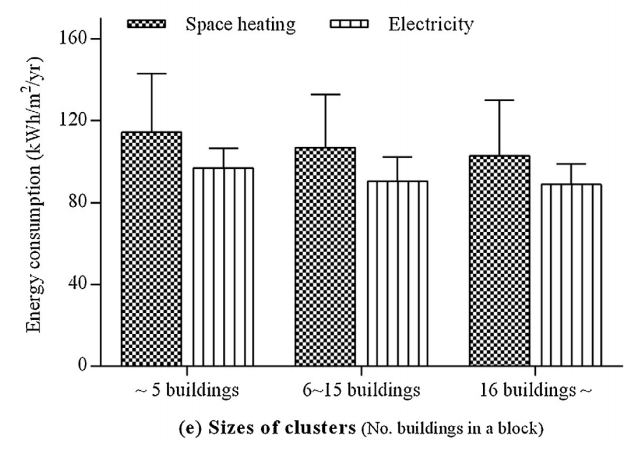

Figure 5 Energy consumption of old apartment buildings by (a) conditions of building envelopes, (b) lengths of buildings, and (c) heating methods, (d) sizes of units, (e) sizes of clusters, and (f) types of building layouts.

First, the most effective reduction was found by improving the condition of building envelopes, which was a maximum 48.7 kWh/m2/year (Fig. 5(a)). In particular, the largest reduction occurred between buildings constructed before 1980 and those constructed between 1981 and 1984. This is because buildings built before 1980 did not have insulation on their envelopes while 50 mm internal insulation were applied for those constructed between 1981 and 1984. The second largest reduction was between buildings built between 1981–1984 and between 1985–1987. This was achieved by replacing the type of glazing in windows from 3 mm single glazing to double glazing. The result indicates the thermal condition of building reduced energy consumption.

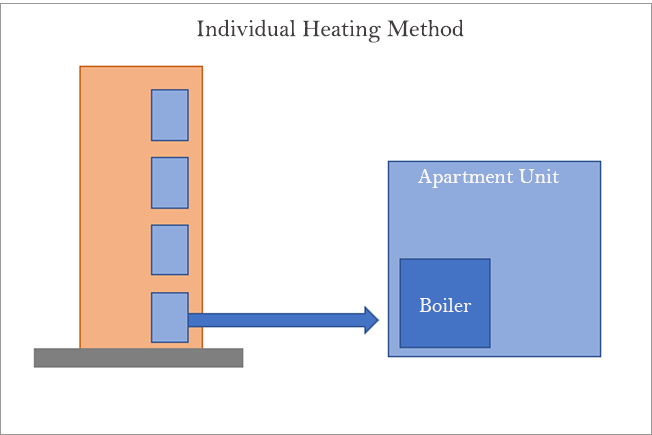

Second, the shorter lengths (that is with fewer vertical access points) the buildings had, the less energy consumed for space heating. Specifically, gradual energy reduction up to 30.2 kWh/m2/year was found by decreasing the lengths of buildings. As the heights of buildings were mostly fixed either 12 or 15 stories, the total amount of surface area, which is exposed to heat transfer, was reduced. Consequently, this was beneficial in reducing energy consumption. Third, the changes in heating methods also reduced up to a maximum of 26.2 kWh/m2/year of energy consumed for space heating. A large gap was found between buildings with central gas heating, and buildings with district and individual gas heating. 24.3 kWh/m2/year was found between central gas heating and district heating, but only 2.0 kWh/m2/year was found between district and individual gas heating.

The opposite tendency is that greater energy consumption occurred in buildings constructed in the late stage. This is due to three features, namely the sizes of building units, the sizes of clusters and the types of building layouts (Fig. 5(d)–(f)). Firstly, the sizes of buildings units were increased in response to higher preference for the large sizes of units. This increase in unit sizes caused higher energy consumption in old apartment buildings, which is nearly 30 kWh/m2/year more energy consumption for space heating and 20 kWh/m2/year for electricity, to maintain a certain level of thermal comfort within the indoor environment.

Secondly, old apartment buildings in large apartment clusters consumed less energy than those in small apartment clusters. The amount of energy reduced according to the sizes of clusters, a maximum 12 kWh/m2/year for space heating and 9 kWh/m2/year for electricity which were not as significant as the reductions for other features. Thirdly, the types of building layout showed increases with 5 kWh/m2/year in electricity from linear to grid.

In short, the six building features are identified as being effective in energy consumption. However, the different amount of energy affected by each building feature needs to be evaluated in order to prioritise refurbishment strategies. The results of these evaluations are illustrated in Section 3.3.

Conclusion

This study aims to identify old apartment buildings in South Korea that need to be refurbished in terms of energy efficiency and suggests how the refurbishment should be done to reduce their energy consumption. It reveals that old apartment buildings constructed between the 1980s and 1990s are those which need to be urgently refurbished. This is because they showed excessive energy consumption for space heating and cooling, compared with the consumption of apartment buildings built in the 2000s. However, maximum 43.65 kWh/m2/year in space heating and 5.70 kWh/m2/year in cooling were reduced in those old apartment buildings in terms of construction years. This reduction was attributed to the transformations of building features in the 20-year period. The eight features in old apartment buildings successfully account for 70.9% of total variance in the factor analysis. The largest proportion, 25.9%, was explained by the factor related to building form and fabric. Multiple regression analysis indicated the three most influential parameters: the thermal conditions of building envelopes with SRC 0.626; heating methods with SRC 0.301; and the sizes of building units with SRC 0.300.

Applications of this approach to cases in the other countries may bring about different building features in prioritising old high-rise apartment buildings for energy-efficient refurbishment. Thus, the refurbishment strategies for each country should take specific features and conditions of the apartment buildings into account in order to suggest efficient policies and regulations for refurbishment in each country.

References

Find the list of the references, accessed by https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2015.03.027